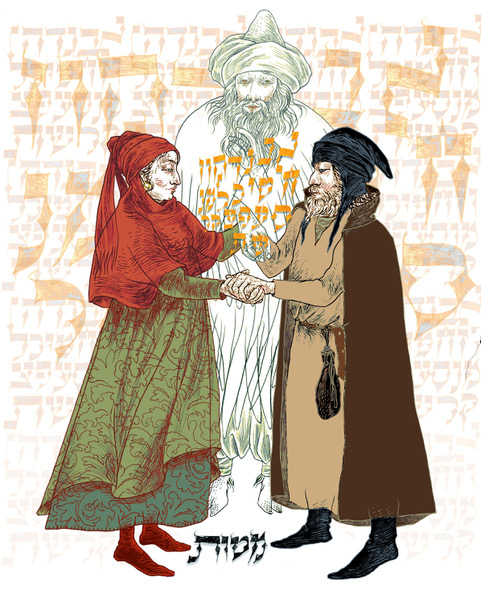

This week’s Torah reading–Toledot–contains the famous story of Isaac “unknowingly” bestowing his blessing for Esau on Jacob. The text tells us that “Isaac was old, and his eyes were too weak to see,” so it’s easy to assume that this meant he was blind, or at least visually challenged enough to not see the difference between his two sons. We know he’s suspicious, because he asks to “feel” his son’s arm–Esau was rugged and hairy while Jacob’s skin was smooth and soft.

Isaac was either fooled or went along with the ruse, blessing Jacob and presumably leaving Esau bereft of both blessing and birthright.

But especially in Torah, things aren’t always as they seem. In telling Esau he wants to bless him, Isaac says, hinei na zakanti lo yadati yom moti, “Here, please, I am old and I don’t know the day of my death.” Esau is told to go hunting and prepare a dish for his father, who will then t’varech’ka nafshi b’terem amoot “give you my soul’s (innermost) blessing before I die.”

One of our ancient sages, Rabbi Eliezer, taught his students that one should repent the day before his death, which of course prompted the question, “How does one know the day of his death?” And he replied, “All the more reason one should repent every day.”

Could Rabbi Eliezer have been thinking about Isaac’s comment when he taught this? If you change the idea of “repenting” to “getting one’s affairs in order,” then the two are totally connected.

Hezekiah ben Manoah, the 13th century French rabbi and Bible commentator known as Chizkuni, has an interesting take on what Isaac night have been thinking. In essence, he understands Isaac’s blessing of Esau and a precautionary measure, that if he were to die suddenly, Esau would lose his money and authority, as he had sold his birthright to Yaakov. By giving Esau his wealth while he was still alive, Jacob wouldn’t be able to challenge it later.

The Radak, Rabbi David Kimhi, also understood Isaac as being concerned about dying suddenly without an opportunity to bless his first-born.

The fear of dying suddenly and unexpectedly and before our time is real; although while we’re young, it’s hard to imagine. For Isaac, who is now 123 years old, the possibility of simply not waking up the next morning is even more of a concern. It makes sense that he might want to tie up loose ends and “make things right,” with Esau, and perhaps even to repent.

Life can change in the blink of an eye. As we’ll see in parashat Vayechi, which translates to “And Jacob lived,” Jacob will call his sons together to bless them; perhaps having learned a lesson from his father.

For many people, experiencing a tragedy motivates them to write a will, say “I love you,” take a trip that’s been put off, and in many respects, begin to live. From Isaac, we can learn not to keep putting these things off, figuring that we’ll take care of it someday.

When my father’s mother was in her 90s, my father convinced her to give the jewelry intended for her granddaughters while she was still alive so she could shep nachas, enjoy seeing us wear and enjoy them. And by giving Esau his inheritance while he’s still alive, as opposed to waiting until he’s gone, not only could “the will” not be challenged, Isaac would see his favored son enjoying and benefitting from his wealth.

Regardless of our financial net worth, we all have an abundance of riches to share with our loved ones. May we learn from our patriarch Isaac and share our blessings with our loved ones so we can share in their joy.

0 Comments