A few weeks ago, my husband and I visited the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan, a place neither of us had been since childhood. Based on many of the exhibits we saw, I’m not sure how much has changed since then, although Pluto was still considered a planet. I did find myself increasingly uncomfortable looking at the thousands of stuffed animals in their “natural habitats,” wishing they would come back to life like they did in “Night At The Museum.”

One thing was quite new, and that was a wall addressing The Statue, referring to the controversial statue of former president Teddy Roosevelt on horseback with an African and Native American standing on the ground. Created by John Russell Pope, The Roosevelt Memorial Commission wanted a memorial that was “intended to express Roosevelt’s life as a nature lover, naturalist, explorer and author of works of natural history.” One hundred years later, the statue is scheduled to be removed at the Museum’s request, as an acknowledgment of our systemically racist history, and as part of an effort to “advance our institution’s, our City’s, and our country’s passionate quest for racial justice…”

What may have seemed acceptable in Roosevelt’s time is no longer acceptable, and while we can’t change the past, we do need to wrestle with it and acknowledge it; the good, the bad and the ugly.

In preparing a study session on the book of Ruth, I came across the Jewish Publication Society’s Bible Commentary: Ruth by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Tikva Frymer-Kensky (z”l) which looks at the parallels between this story and the Torah. The authors write that “These intertextual connections serve many purposes. For example, they allow the story of Ruth to right wrongs; redeeming, as it were, things gone awry in Genesis: [including] Ruth’s integration into the family of Boaz [which] repairs the breach between Abraham and his nephew;” along with other situations.

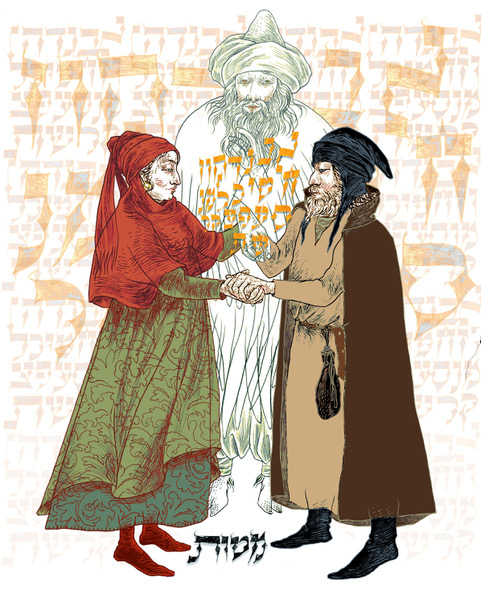

For many reasons, the story of Sarah and Hagar, “which climaxes with the expulsion of the young foreign woman by the elderly Israelite insider, finds its resolution when the elderly Naomi and the young foreign woman, Ruth, bond and support each other.” Notice that this isn’t meant to redeem, explain or erase what Sarah did; it acknowledges that it happened, and that perhaps, society’s rules have changed. While the Torah tells us that Moabites (descendants of Lot) aren’t allowed into the Israelite community, Megillat Ruth embodies the Torah’s commandment to “love the ger, ‘stranger,” and to treat them as one would treat a citizen. Not only does the community accept and welcome Ruth; because she becomes the great-grandmother of King David, the story comes full-circle.

Individually and collectively, we all have things in our past that we’re not so proud of now, and that’s life. The question is, how do we handle things moving forward? Removing the statue from AMNH won’t change or cancel-out the past, but if it makes us stop and think about how we view our heroes (because no one builds monuments to mere mortals) and fosters discussion that acknowledges the humanity of all, I can live with that.

This is a moving and lovely drasha. It has given me a lot to think about. Thank you, and Chag Samayach !

Thank you, I look forward to hearing your thoughts! Chag Sameach and Shabbat Shalom.