akedah mosaic at Beit Alfa, Wikimedia.org

VaYera: Is Our Story Abraham’s?

by Rabbi Richard Address, D.Min.

Parashat Vayera offers us so many challenges, so many glimpses into issues that touch on so many of our experiences. The reading begins with the mitzvah of welcoming the stranger and the textual basis for the mitzvah of bikkur cholim (visiting the sick) and concludes with the challenging and frightening act of Akedat Yitzchak (the binding of Isaac). It’s so much like our lives, in that we have both the tendency for kindness and the conflict with children, a conflict that is played out throughout the parashah.

No, Abraham’s family is no model of perfect family dynamics. But then again, how many are? As we age and review our own lives, how many of us can see elements of our experiences within this parashah?

Among the several ethical and moral tests that the portion contains is one that leaps right out of contemporary culture. Right off the bat, we encounter the famous story of Sodom and Gomorrah. Abraham is told of the impending destruction, and he assumes his moral high ground in a debate with God asking–or challenging God (18:23)–“Will You sweep away the innocent along with the guilty?” What follows is a spirited debate and bargaining regarding the minimum number of innocents that will be needed to save the cities. Shall innocent people be hurt because others have acted badly? We are seeing this debate played out now in the so-called “cancel culture” discussions.

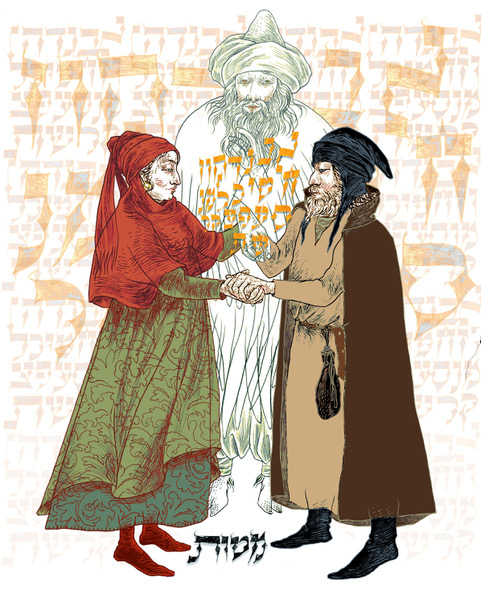

Abraham assumes the moral high ground, going one-on-one with God. But then, he’s confronted with Sarah and her demand that he expel Hagar and Abraham’s first-born son, Ishmael, from the camp. Is this the jealousy of two mothers vying for the affection of the father, or sibling rivalry, or the failure of so-called “blended families” to adequately integrate children from various prior arrangements? Does Abraham tell Sarah, “No, I will not expel my son”? No. He runs to God who tells him sham b’kolah, to do what Sarah wants. No argument this time from our Patriarch. It seems easier for Abraham to argue for the innocents of the cities than to argue for the life of his first-born. As so many of us look back from where we came, how may of us regret time spent in pursuit of career and material things rather than those moments with family, moments that can never be recaptured!

Then there is the famous and always puzzling incident in chapter 22 and God’s call to Abraham to take his son to a certain place and prepare him to be sacrificed. Indeed, Isaac does become bound by his father–only to be rescued as the knife is about to fall. So many commentaries have been written on this passage. So many parents have acted this way; sacrificing their children on an alter of personal ego and unfulfilled dreams. How many of our children grew up being “bound” by the unrealistic expectations of their parents? How many families have seen significant disputes between parents on raising children, and how many of our children have been cast out because they were different or didn’t conform to a preconceived notion of what mom and or dad desired? How many stories, from Torah to Star Wars, in the end are about these delicate relationships between children and parents?

One can only imagine the impact of the trauma of these events on the boys. Ishmael is expelled and Isaac is taken to be sacrificed. Is it any wonder then that the two sons grow apart? They meet only once more to attend their father’s funeral and according to the text, do not even meet for Sarah’s. So is it any wonder that, according to Torah, Isaac and his father do not speak again? How many families live with estrangement for years, perhaps decades?

The intricacies of family dynamics are all displayed in this Torah portion. Commentaries abound as a result of these verses. This portion is so contemporary, and so many of our stories are represented. Even as the portion ends, and we see Abraham journey down the mountain alone save for his servants. Isaac is gone? Was he so angry that he could not stand being with his father? Does he vanish?

Or, as some commentaries suggest, does the incident on the mountain liberate Isaac? Indeed, Rabbi Gunther Plaut suggests, in his Torah commentary, that “in the binding Isaac becomes an individual in his own right” (Plaut Torah Commentary. P.152). He cannot escape the traumas of his childhood, but this event frees Isaac to become his own person. How many families have lived this story that a child is freed to become their own self only after some traumatic event with the family?

The beauty of the Torah in general, and portions like this in particular, is that we are shown Biblical personalities as real people. No heroes these men and women. They are tested by life and, like us, sometimes succeed and sometimes fall short. Like us, they are human beings who struggle to find meaning, purpose, community, and love. Like us, as we review our own journey, we can find examples, situations and parallels in our lives that speak to the challenges and tests of our Biblical family. This is a call from our own tradition to us as we strive for a mature spirituality that comes from a living tradition and that, in a way, we are all Abraham’s children.

Rabbi Richard F Address, D.Min is founder and director of Jewish Sacred Aging®, the web site jewishsacredaging.com and hosts the weekly Seekers of Meaning podcast.

0 Comments