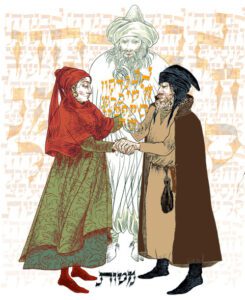

Illustration ©2009-Ilene Winn-Lederer

Mattot: What Words Can Create

Ilene Winn-Lederer

Although I grew up with a strong Jewish identity, I did not experience a traditional Jewish education and came to Torah in my late teens through influential involvement with a Jewish youth organization called ATID (Hebrew for “future”). A few years later, contacts within the Chabad organization offered another perspective. Still, much time would pass before I understood that having a Jewish soul implies–through thought and behavior–an instinctive understanding of worthy character traits or middos and Torah principles even without the ability to quote chapter and verse in an ancient language.

Perhaps this understanding can be described as the legendary pintele Yid, the tiny voice inside that speaks to us when we are listening and guides us in our endeavors. Could this tiny voice be a remnant of “when we all stood at Sinai”? Is it this invisible entity that ensures the continuation of the Jewish people in spirit throughout the blessings and horrors of our history? Such questions and my curiosity led me down a winding path to studying Torah liturgy and commentaries that ran the gamut from Talmud to Midrash to folklore and mysticism. Each step on this path informed my work as an artist, illustrator, and writer, culminating in a project to create a book that I wished I’d had as a young person to help me understand this essential part of myself.

So what does all this have to do with Parashah Mattot?

After 25 years, the aforementioned book project was published as Between Heaven & Earth: A Visual Torah Commentary in 2009. It includes illustrations and commentary for each of the 54 Torah parashiyot of which Mattot is the ninth and penultimate reading[1] in BaMidbar, the Book Of Numbers.

When I was invited to contribute to this volume, my first choice was Parashat Mattot for its focus on the meaning and power of words and the attendant laws of oaths, vows and promises for their ability to alter our perceptions and the nature of our current reality.

I also found this parashah interesting because as it helps complete the Book of Numbers, it confirms the origin of Torah as the words of God and emphasizes the importance of verbal vows and actual commitments. The placement of Parashah Mattot leading up to the “last word,” conveys the power of that message.

Even as I worked to create visuals for my book, my mind kept insisting that I explore the origins of language; how it develops and influences all we see, hear and experience. So, according to Torah, God created the world with words. Before these words of creation were spoken, “existence” was a “void,” a “nothingness” of abstract potential, a blank canvas, so to speak, for God to envision and create everything with words and letters as building blocks.

Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism posits that each component of creation has a name in the Holy Tongue and that each letter of those names is a gateway for a specific Divine energy continuously working together to create the reality in which we function. However; it also notes that Creation was not a one-time event, rather it was the initiation of a process that continues to exist and be ‘reborn’ by the grace of God’s timeless utterances. There can be no room for entropy in this way of thinking.

In Bereshit, the Genesis narrative, language was gifted to Adam upon his creation and subsequently to all humans to distinguish us from all myriad life forms on Earth.

Yet, in Judaism, a covenantal belief system, the ability to vocalize our thoughts is a duality. Why? Because beginning with the binary nature of our Creator itself, the concept of duality permeates all of Creation. Nothing can exist without its opposite: life and death, good and evil, heaven and earth, male and female, etc., so we were given the use of language with the proviso that beyond describing something, it can be used to initiate an action such as a promise made between two or more persons, and by extension, to Our Creator. When an action is completed, it becomes an accomplished fact, new reality. This alone dictates that oaths, vows and promises imply trust and are the basis of an orderly, free society.

My choice was also influenced by my beloved grandmother’s words at the end of her life in 1977. Though I don’t recall the context, they were: “Be careful what you say, because once words are out of your mouth, you don’t own them anymore.”

In the years that followed, her words became the foundation of my thinking as I developed personal, professional and communal relationships, acutely aware that spoken words can harm as well as heal. Moreover, words spoken in anger are only the product of heightened emotions and can hurt if taken literally and personally.

When, as a child, I would come home in tears because another child said something hurtful to me, my mother would comfort me with the admonition to ‘consider the source,’ meaning to step back and put such words in perspective regarding my relationship with that other child. I learned to listen between the lines for the emotional quality and potential motives behind them and respond accordingly.

Now, in this third quarter of my life, having been a Jewish daughter, then a mother and now a grandmother, I’ve not forgotten those early lessons in communication and strive to impart them as a frame for my personal and professional legacy with the following thought: When our words are words of love, respect, Torah and prayer, our every utterance transforms the mundane world around us into a place of holiness.

[1] Most years, parshat Mattot is read along with Masei, to complete the book of Bamidbar. In leap years it’s read by itself.

From the moment I first saw Ilene’s artwork, weaving together calligraphy, concepts, and fantastical images in “Illiminations” I was smitten and inspired! Thank you for sharing your artistic gift and wisdom with our world!

Yikes! Spell Check!! Illuminations!