Photo Credit: Rabbi Susan Elkodsi

In the interest of full disclosure, I’m not a grandparent, but I had grandparents, and so did my children. Yes, there are some kids who call me “Rabbi Grandma,” but that’s not quite the same thing.

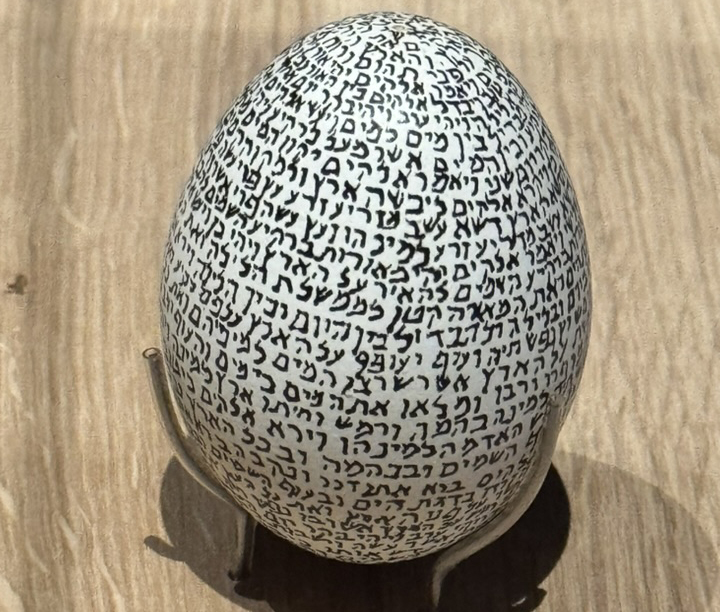

Under most circumstances, I would have glossed over Genesis Chapter 48 in this week’s Torah reading, simply mentioning that it’s from this text–when Jacob blesses his grandsons–that we get the traditional Erev Shabbat blessing for our sons, Y’simcha Elo-him k’ephraim v’khi menashe, “May God make you like Ephraim and Menashe.” (Gen. 48:20). However, this week, I’m participating in an intersession class at the Academy for Jewish Religion called, “Who Are Our Adult Learners?” with Susan Werk. On our first day, we looked at this chapter, and how it might relate to and resound with Baby Boomers and older Jewish adults.

In fact, when we take a deeper dive into the 23 verses that make up this chapter, we find so many things that might parallel the grandparent-parent-grandchild relationships in today’s world. The chapter begins with Joseph being told that his father is sick, and he takes his sons, Menashe and Ephraim, to visit.

Jacob sits up and says, “El Shaddai, who appeared to me at Luz in the land of Canaan, blessed me and said to me, ‘I will make you fertile and numerous, making of you a community of peoples; and I will assign this land to your offspring to come for an everlasting possession.’ Now, your two sons, who were born to you in the land of Egypt before I came to you in Egypt, shall be mine; Ephraim and Manasseh shall be mine no less than Reuben and Simeon, but progeny born to you after them shall be yours.” (Gen. 48:3-6).

Does this mean Jacob is adopting Joseph’s sons, or claiming them as his own? Is this a commentary on Joseph’s parenting ability, or the concern that they’re not being properly raised in Jacob’s faith? It’s often said that “grandparents and grandchildren have a common enemy.”

Jacob and Joseph were reunited about 17 years earlier, during the second year of the famine. The Torah doesn’t tell us if Joseph’s sons were included in that reunion, or if now, all these years later, Jacob is meeting them for the first time. Since we have no record of Joseph visiting his family in Goshen, we might surmise that Joseph didn’t have much interaction with–or much in common with–his family of origin. And another question, was Jacob even aware before now that Joseph had sons?

While I was blessed to raise my children in the town where I grew up, where my parents z”l also lived, that may be the exception in today’s world, rather than the rule. Many grandparents don’t get the joy (or the oy) of seeing their grandchildren on a regular basis, being able to attend their school and extracurricular events, and getting together at the drop of a hat. When families are hours or even continents away, and visits are infrequent and perhaps come with additional challenges, it’s a whole different dynamic. Video chats and phone calls are great, but they’re not the same thing as being in the room together.

What about Jacob’s other grandchildren? After all, he has 11 other sons, and we know they had children, because the torah includes the genealogy. In this scenario, however, we have no idea where they are, perhaps because Jacob still favors Joseph, and by extension, his sons. What happens when grandparents play favorites, or they can’t give equal attention to their grandchildren? My niece and nephews, who grew up an hour and a half away in New Jersey, certainly didn’t have the same relationship as my children did, even though they were no less loved.

The age and wellbeing of the grandparent also comes into play. In verses 9-10, Jacob asks, mi ayleh? “Who are these?” The Torah tells us that Jacob couldn’t see (clearly) and could only distinguish shadows (Steinsaltz). When Jacob replies that they’re the sons God has given him, Jacob asks that they be brought closer to him, and he kisses and embraces them. Those of us of a certain age might remember our cheeks being pinched by our grandparent-aged relatives, or being forced or persuaded to give hugs and kisses when we might not have wanted to. Today, our children are–rightly so–being taught that no one is allowed to touch them without their permission, which can leave an affectionate grandparent feeling rejected. We don’t know the ages of Joseph’s sons; they could be preteens, or, given that Joseph was about 30 when they were born, they could be closer to their 20s. How does Jacob’s behavior sit with the parent in the middle?

Finally, when Jacob blesses the boys, he puts his right hand on the younger one’s head, essentially elevating him to the status of “first born.” Has he learned nothing from his experiences where the younger was elevated over the older? Joseph tries to correct his father, but Jacob makes it clear that he knows which one is which. Should he have challenged his father in front of his sons? What sort of example does that set for the sons?

The Torah refers to the 12 Tribes of Israel, Joseph’s sons, but if you look at the list, you’ll notice that there’s no tribe of Joseph, there are the two half-tribes of Ephraim and Menashe. Jacob’s bequest skipped Joseph and went to his sons. Depending on how old we the grandparents are, and how old their children are, it’s not unusual for the elders’ inheritance to be bequeathed directly to the grandchildren, especially when their parents are financially secure.

Jacob gave the blessing of progeny to his grandsons along with his blessing. He’s fully aware which son is which, and perhaps has a prophetic gift that Joseph doesn’t have. By blessing and acknowledging both sons, Jacob’s legacy is passed on to the first set of brothers in the Torah who don’t openly quarrel.

May we merit to be a blessing to our grandchildren, our “honorary” grandchildren and future generations.

Thank you to my classmates for sharing their Torah and making this class special.

0 Comments