Dome of KKBE, Charleston, SC by Rabbi Elkodsi

Emor: Questioning The Status Quo

Dr. Betsy Stone

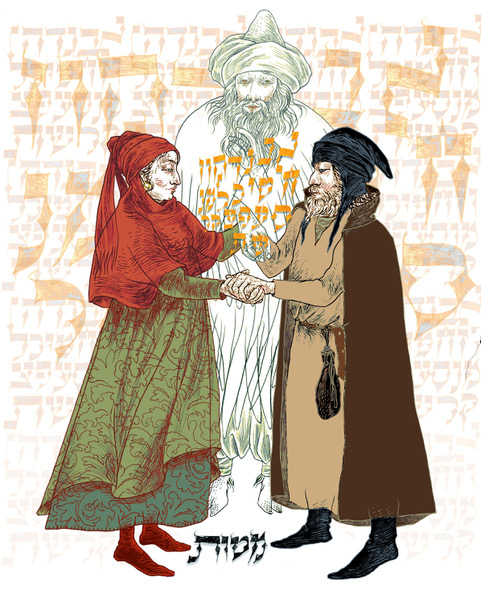

I am fascinated by this parsha, with its juxtaposition of HOLY days and UNHOLY people. Emor begins by telling us how a Kohen may be defiled/ritually impure–by visiting a graveyard, shaving parts of their heads or cutting themselves, by marrying a divorced woman, by going unshaven or leaving the Temple. It continues with a description of all the people who may not even visit the Temple to bring a sacrifice; those with weeping sores, long eyebrows, broken limbs, the blind, or the lame.

Of course, these distinctions are disturbing. Why is a person with a defect (Torah’s word, not mine!) of lesser value? Why is a divorced person unfit to marry a Kohen? What are we to learn about ourselves if these standards are applied?

In a world of social media and curated selves, don’t these distinctions between people create a value hierarchy, a message that only the most perfect matter? Or at least that we Jews exist in an internal hierarchy, with virgins and perfect physical specimens at the top of the list, just below the Kohanim?

Where does this leave us as we age? Does the wisdom of aging balance the inevitable losses of beauty?

The text then takes us to the schedule of Holy Days, days which require much of each of us, without regard to status. The outline of required behaviors includes everything from what we bring for sacrifices to what we eat. This calendar reminds us that we exist both in relationship with God, and in relationship with others. While God may require animal sacrifices and a cessation from work, these weekly and yearly reminders of our relationship with God also remind us that we live in community.

A Kohen can keep serving in his position for as long as he is able; unlike the Levites, he’s not forced to retire from active service at 50. Does his wisdom override the perceived loss of stamina?

Research on spirituality teaches us that our spiritual interests often rise towards the end of life. As we leave the hustle and bustle of the working world, many of us turn towards the deeper questions of life: Why am I here? What do I leave behind? Has my life had meaning?

How do we understand the juxtaposition of holy days and unholy people? It seems clear that each of the Holy Days requires action on the part of each of us. When we read that the blasphemer must be banished from the community (Lev 23:30); it suggests that there is some understanding that what unites the community is the shared relationship with God, and that one who disrupts that relationship cannot be accepted.

But what if we saw this parasha differently? There is a burden in being isolated, in being different, in being unable to make one’s own choices. Maybe the Torah is teaching us that everyone, regardless of status, must follow rules that can challenge us. Whether it’s the loneliness of the High Priest, or the obligations of Shabbat and Holy Days, these rules are not there for our comfort, but for a deepening relationship; with God, with each other, with a world we are often on the edge of. Maybe, even a more profound understanding of what it is to be “other.”

Is it possible that the message of Emor is that we are all “other”? Whether we live with privilege and status or in poverty and despair, what we have in common is the obligation to act towards the needs of the group over my our own personal wants. When I clear the hametz from my home for Pesach, when I pause for Shabbat peace, when I fast–all of these are opportunities to remember that I am obligated. Obligated to God, to the Jewish people, to all people.

How do these ideas apply to questions of aging? As we age, our status often diminishes. We may move from a position of power and respect to one where we feel passed over, less important. How do I absorb this lessening of honor? Is my wisdom and life-experience really worth less than it was?

I am therefore obligated to return to our opening ideas–that some are less worthy, less able, less included. I confess, I cannot get comfortable with this idea. I can justify the writing by thinking of the different mores of behavior in other times. But maybe my discomfort is actually the lesson here. The Torah does not promise me comfort, nor does it always live up to the standards of our time. It promises challenge and deep reading. Some times are holy, but no one person is less than hol–whether it is my enemy or the homeless or the less-abled. It behooves me to remember that.

Holy days and the rituals that accompany them are designed to bring us together to embrace our shared heritage, and to pass along our traditions to future generations. This parashah also reminds us that even though there are some categories of people who are prohibited from performing various ritual acts, they’re still part of the community and must be welcomed and cherished as such.

0 Comments