Parashat Beha’alotekha: Lessons from the Elders

Cantor Sandy Horowitz

At the start of the Covid pandemic, those of us over age 55 were warned that we were the most susceptible to this deadly virus. As I entered into complete isolation, for the first time in my highly independent and productive life, I became the recipient rather than the provider of care and concern. Younger family members and friends delivered groceries and ran errands, gave advice, and worried. I confronted the fact that I was now part of “that” demographic, which led me to thinking about the nature of growing older, not just during Covid, but in the culture at large.

Often, being older means having to strive to look and act younger; despite the inevitability of the aging process, we continue to be measured by our productivity. “He’s so active for his age!” “At her age she still looks great!” As I reflected on my own aging process, I wondered about this emphasis on productivity and accomplishment. Parashat Beha’alotekha offers three different models of aging, in the narratives of the Levites, the elders of Israel, and Miriam.

In Numbers 8:24-26 we read about Levite service: “From the age of 25 years and upwards, he shall enter the service to work in the Tent of Meeting. From the age of 50 he shall retire from the work legion, and do no more work. He shall minister with his brethren in the Tent of Meeting to keep the charge, but he shall not perform the service.”

Retirement at age 50, imagine! It’s understandable though: the work of the Levites was physically demanding as they prepared the sacrificial offerings and were responsible for the upkeep and transport of the mishkan, the portable sanctuary. But as we just read, retirement for the Levites did not mean complete cessation from work. The 11th century commentator Rashi suggests that the tasks of the over 50 Levites might have included locking the gates, singing, and loading the wagons when it was time to move on. By taking on more age-appropriate tasks, they remained valuable members of the Levite clan.

Now let’s consider the elders of Israel. In this week’s Torah portion, when the Israelites complain about the manna that God had been providing and demand meat instead, an exasperated Moses appeals to God for help. God tells Moses, “Gather Me 70 men of the elders of Israel…and bring them to the Tent of Meeting that they may stand there with you. And I will come down and talk with you there, and I will take of the spirit which is upon you, and will put it upon them; and they shall carry the burden of the people with you, that you carry it not yourself alone.” (Num 11:16-17)

The elders of Israel appear a number of times in the Torah narrative. Back when Moses first encountered God at the burning bush and received God’s instructions with regard to confronting Pharaoh, Moses was told to bring the elders of Israel with him, that they should stand with him when he demanded freedom for the Israelite people.

Later, after the newly liberated Israelites were on their way to Sinai, the people began to complain about lack of water. When Moses sought God’s help, God instructed him, “Go before the people, and take with you the elders of Israel, and your rod…I will stand before you upon the rock in Horeb, and you shall strike the rock, and water shall come out of it… and Moses did so in sight of the elders of Israel (Ex 17:5-6).

In each of these instances (and others not cited here), the power of the elders does not come from any particular action on their part. Rather, it is their age and stature within the community that lend authority and legitimacy to the actions being taken by Moses. I’d like to think that for Moses, the presence of the elders also provided him with much-needed spiritual and emotional support.

We now come to the difficult story regarding Miriam which takes place in Parashat Beha’alotekha. When she and Aaron speak out against Moses for marrying a Cushite woman, God punishes Miriam–she is smitten with skin disease and exiled from the community for seven days.

Miriam’s bad-mouthing of Moses is out of character from what we know of her. Her appearances in the Torah narrative, while sparse, suggest that she has been a loving supporter of her brother and his efforts to lead the Israelite people. I believe she may well have been suffering from exhaustion and burnout, here at the end of her long life.

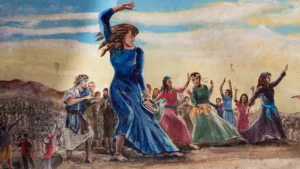

As a child, it was Miriam who saw to it that Moses would have their mother as nursemaid after he was rescued from the Nile by Pharaoh’s daughter. Later, after the newly freed Israelite people crossed the Sea of Reeds, it was Miriam who led the women in singing and dancing. She is referred to as “prophetess” in the text; it is she who transforms the traumatic experience of liberation from slavery into a much-needed moment of celebration and joy (Exodus 15:20).

Midrashic literature tells of how Miriam’s mysterious well provided water for the Israelite people whenever they needed it throughout their journey until the day she died. At our Passover seder each year, we pass around the Cup of Miriam, as each person takes water from the Cup while reflecting on what it is we need most at that moment; together we then thank Miriam for her gift of sustenance. Miriam was always providing for others; in this light her transgression and its consequence are all the more painful to witness.

I choose to regard Miriam’s story as a reminder to recognize my limits as I age, and to know when it’s time to slow down and take a break before I say or do something I’ll regret. The Levites’ retirement strategy teaches me that doing less is not a character flaw. And the recurring presence of the elders of Israel reassures me of the intrinsic value of simply being present, in body and in spirit.

Sandy Horowitz is the Cantor at Beth Am The Peoples Temple in Washington Heights, New York. She has worked in Jewish education with both children and adults, enjoys composing and writing, and just recently retired her massage therapy practice after more than twenty years in that field. Cantor Horowitz was ordained in 2014 at the Academy for Jewish Religion and holds a Masters in Jewish Education from Gratz College.

0 Comments