Photo credit: publicdomainpibtures.net

Shabbat for the Fourth of July

Two hundred and 46 years ago, the Continental Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration of Independence, and in addition to stating a litany of grievances against tyrannical British rule, they declared the 13 Colonies to be an independent union, the beginning of the United States of America. It’s well know that history is written by the victors, and my British friends tell me that what they were taught growing up was that “the colonies were too difficult to govern from across the pond, so they gave us our independence.” If only it had been that easy. If only Pharaoh had let the Israelites leave Egypt the first time Moses asked.

Giving birth is rarely easy but for most mothers, the pain of childbirth pales in comparison to the brand new life they’ve just brought into the world. For most first time parents, this awesome moment is immediately followed by fear and trepidation. We do our best–considering advice from our parents, family members and experienced, well-meaning friends–and pray that our best will be good enough.

Giving birth to a nation is similar; a government is formed, discussions are held about who will do what and who gets to participate, documents are drawn up, and declarations are made. Those who will be in charge need to figure out how to integrate the various groups that make up the society. Infrastructure needs to be created, and laws need to be established.

In colonial America, many of these rules were set down in the Constitution and other documents. Shortly after the Israelites left Egypt, the Torah was revealed to them from Mount Sinai. We publicly read the Aseret haDibrot, usually translated as the Ten Commandments, three times during the year; in the winter when we read parashat Yitro, on Shavuot, and during the summer, in parashat Va’etchanan when Moses reiterates them with a few minor variations. The prayer “Lecha Dodi” comes from one of those variations, but that’s a discussion for another time.

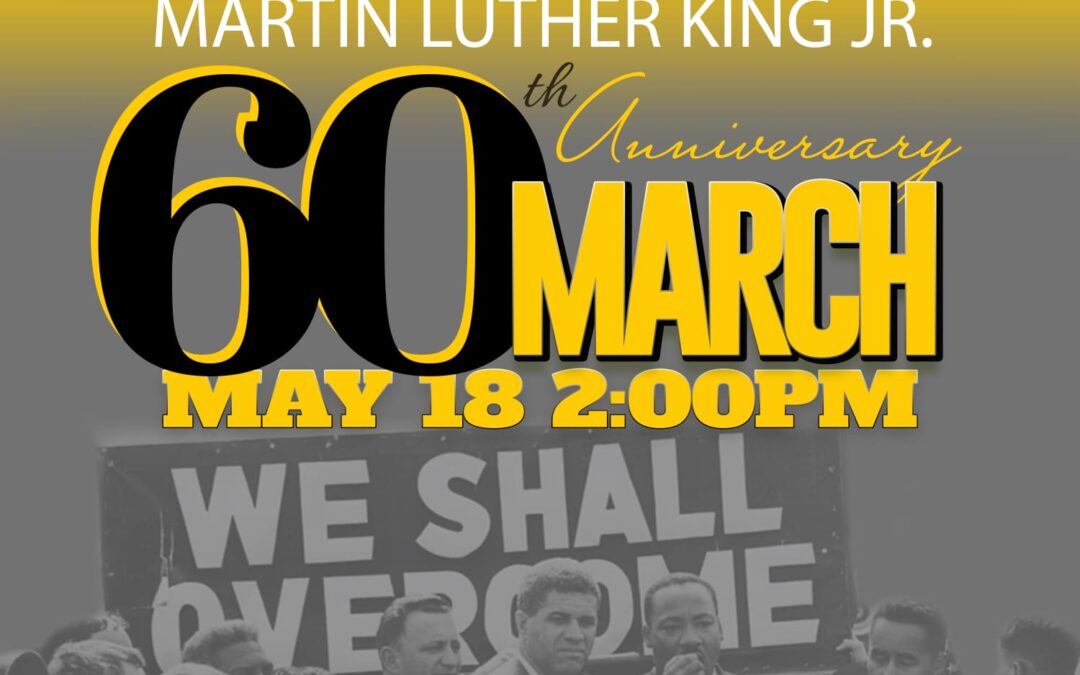

When we think of the Declaration of Independence, we usually think of the phrase, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” This declaration became a “call to arms” for civil rights and was the cornerstone for Lincoln’s Gettysburg address and his policies while in office.

While this certainly isn’t a direct quote from Genesis, it parallels the idea that God created humans b’tzelem elo-him, in the Divine image, and that we are all descended from one Supreme Creator. The Talmud asks, “Why was only a single specimen of man created first? In order that no race or class may claim a nobler ancestry, saying, ‘Our father was born first’; and to give testimony to the greatness of the Lord, who caused the wonderful diversity of mankind to emanate from one type.”

The emerging union that was fighting for its independence and for the right to self-government, was made up of a multitude of diverse populations and communities. For more than a century people had been making the journey across the Atlantic to the New World. Many were escaping poverty and famine in Europe, hoping to find greater economic opportunity and new markets. Others left their homelands to escape religious persecution, although many found that this persecution followed them.

In 1776 there were approximately 2,000 Jews living in various parts of the country. Although a smattering of individual Jews and families had been here for years, the first significant Jewish immigration to these shores occurred in 1654 when Spain defeated the Dutch and recaptured Recife, Brazil, bringing the Inquisition with them. Twenty-three Sephardic Jews who left Recife and sailed north from landed in New Amsterdam. Let’s just say they weren’t warmly welcomed, and had it not been for pressure from the Dutch West India Tea Company, which had many Jewish investors, they’d still be sailing up and down the coast. It was ironic that a country such as ours, founded on principles of religious freedom, was intolerant of religions other than those of our founders. Jews were prevented from entering certain professions and living in certain areas, but fared much better than many of the Catholics who had immigrated here.

Even though there were many laws restricting the rights of Jews and other non-Christians in the colonies, there was a significant Jewish presence during the Revolutionary War and the years leading up to it. Haym Solomon, a Polish immigrant of Sephardic descent, provided significant financial support for the war efforts and was active in both Jewish and US political affairs. Francis Salvador, the first Jew elected to public office in the colonies, was also the first Jew to die fighting for American freedom. Mordecai Sheftall of Savannah, Georgia was the highest ranking Jewish officer of the colonial forces. Almost all of the adult Jewish males in Charleston, South Carolina fought in the war.

The settlers who first came to this country wanted the freedom to practice their version of Christianity, which was at odds with the Church of England, and being devout in their beliefs, wanted to build a country whose society would operate based on the Hebrew Bible. These immigrants saw themselves as re-enacting the Exodus from Egypt. Instead of fleeing Pharoah in Egypt, they were fleeing a tyrannical king in England. The Atlantic Ocean was the Red Sea, and America was their Promised Land.

E pluribus unum, the motto adopted to appear on the Great Seal of the United States, is usually translated to mean “Out of many, one.” Initially, it probably meant that many colonies or states would form one country, but in keeping with the concept of the melting pot, which is what many consider the US to be, it can also mean that out of a number of diverse ethnic, religious, racial and political groups, we have one united, homogeneous society. The reality is that unlike a melting pot, where a variety of ingredients blend together to create something uniform, American society is more like a stew, or as one of my teachers, Dr. Jerome Chanes, put it, cholent (a stew often made for Shabbat lunch). Separate and distinct components each lend their special flavor to the dish, but they still retain their unique shape and character.

We are told in the Torah that an “erev rav,” a mixed multitude, left Egypt and crossed the Red Sea. In addition to the Israelites, there were many Egyptians and others who chose to join them. Our tradition teaches that every Jew, and every convert to Judaism, present and future, witnessed the revelation at Sinai. We can’t really say the same for the American Revolution, but I think we all share a sense of awe and pride to be living in a country that, while it isn’t perfect, allows us to live openly and freely as Jews, and where our ability to exercise our right to practice our religion is guaranteed.

Concluding his letter to the Jewish community of Newport, Rhode Island, then President George Washington expressed the ideal relationship among the government, its individual citizens and religious groups. He wrote, “May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.” This last phrase comes from the book of the prophet Micah, Chapter 4, verse 4: V’yashvu ish tachat gafno v’tachat t’aynto v’ayn macharid. The verse before, Lo yisah goy el goy cherev, lo yilm’du-od milchama, is part of the prayer for our Country, “national shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

The ancient Israelites struggled for independence from Egyptian slavery, and struggled many more times through various wars and the destruction of both Holy Temples. Centuries of struggles, along with the commitment of many visionaries, led to the modern day State of Israel, and while she has made remarkable progress in becoming a modern nation, continues to struggle to secure safety and security for her citizens.

Today we celebrate the struggles of our founding fathers, the visionaries who believed that a self-governing republic on our shores was possible. We stand on their shoulders while we reap the benefits of what they have sown. May we see the day in our land when people of all races, religions and nationalities can live together, where no one needs to fear his neighbor, and where all are willing to work together to keep the United States of America truly “the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

0 Comments